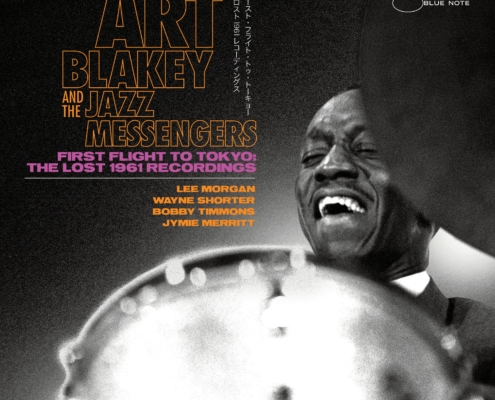

Art Blakey – First Flight To Tokyo The Lost 1961 Recordings

UNVERÖFFENTLICHTE LIVE-AUFNAHME VON 1961!

- Now’s the Time – Take 1 (21:58)

(Charlie Parker) - Moanin‘ (12:44)

(Bobby Timmons) - Blues March (10:59)

(Benny Golson) - The Theme (00:32)

(Miles Davis) - Dat Dere (11:03)

(Oscar Brown / Bobby Timmons) - ‚Round Midnight (12:15)

(Thelonious Monk / Bernie Hanighen / Cootie Williams) - Now’s the Time – Version 2 (16:47)

(Charlie Parker) - A Night in Tunisia (10:30)

(Dizzy Gillespie / Frank Paparelli) - The Theme – Version 2 (00:32)

(Miles Davis)

Art Blakey – drums, Lee Morgan – trumpet, Wayne Shorter – tenor saxophone,

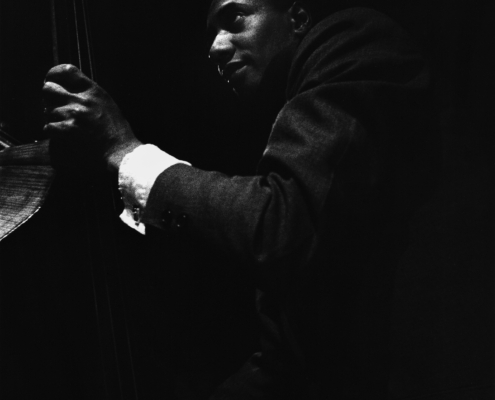

Bobby Timmons – piano, Jymie Merritt – bass

Aufgenommen live in der Hibiya Public Hall, Tokyo, am 14. Januar 1961

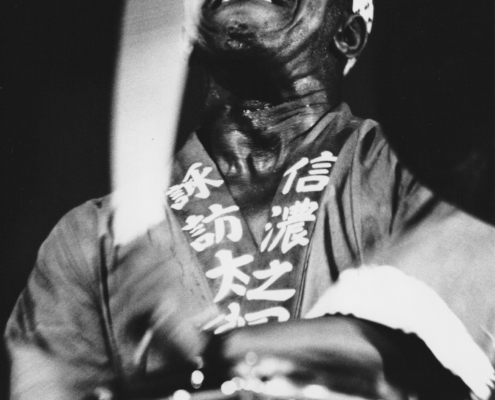

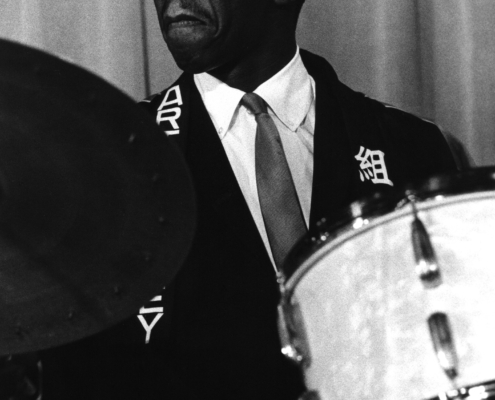

Seine kraftvolle, polyrhythmische Spielweise war das Markenzeichen von Schlagzeuger Art Blakey. Der war nicht nur eine Größe, sondern auch eine besondere Integrationsfigur des Jazz: in seinen Jazz Messengers spielten viele Berühmtheiten bevor sie international bekannt wurden – Art Blakey machte sie erst groß.

Roland Spiegel beschrieb die Legende, die am 11. Oktober 2019 hundert Jahre alt geworden wäre, zu seinem Geburtstag im Bayerischen Rundfunk so:

Vom ersten Takt an ein klares Statement: griffiges Thema, markanter Rhythmus, starke Dynamik – so klang Musik unter der Leitung des Schlagzeugers Art Blakey. Sie hatte mitreißenden Schwung. Die Melodien waren einfacher und klarer umrissen als noch ein Jahrzehnt zuvor, als der „Bebop“-Stil die Töne und manchmal auch die Auffassungsgabe der Zuhörer mächtig durcheinandergewirbelt hatte. Diese Musik hier wollte sich mitteilen, Hard Bop nannte man sie wegen der härteren Konturen. Sie hatte Blues und Soul, viel archaische, schwarze Musik schwang im Hintergrund mit bei diesem Jazz-Stil, für den Art Blakeys Band die Keimzelle wurde.

Den Hunger der weltweiten Jazz Community nach Art-Blakey-Aufnahmen konnte auch das im Juli 2020 weltweit erstmals veröffentlichte Album „Just Coolin‘“ von 1959 nicht stillen. Daher stieg man bei Blue Note Records jetzt ein weiteres Mal in die Archive und förderte diesmal eine bislang unveröffentlichte Liveaufnahme zu Tage.

„First Flight To Tokyo: The Lost 1961 Recordings“ fängt einen großartigen Konzertabend der Schlagzeuglegende mit der klassischen Besetzung seiner Jazz Messengers ein: Trompeter Lee Morgan, Tenorsaxophonist Wayne Shorter, Pianist Bobby Timmons und Bassist Jymie Merritt. Aufgenommen wurde das Konzert am 14. Januar 1961 in der Hibiya Public Hall in Tokio, während der ersten Japan-Tournee der Band.

Die Deluxe-2-LP-180g-Vinyl-Edition und die 2-CD-Edition werden mit aufwendigen Booklets ausgestattet sein, darin seltene Fotos aus dem persönlichen Archiv der Blakey-Familie und denen der japanischen Fotografen Shunji Okura und Hozumi Nakadaira, eine Reproduktion des japanischen Konzerttourneeprogramms von 1961, ein historischer Essay des renommierten Jazzkritikers Bob Blumenthal plus neue Interviews mit Jazz-Ikone Wayne Shorter im Gespräch mit Blue Note-Präsident Don Was, dem gefeierten Blue-Note-Saxophonisten Lou Donaldson, dem japanischen Jazzstar Sadao Watanabe, der renommierten japanischen Musikkritikerin Reiko Yukawa, Art Blakeys Sohn Takashi Blakey und einem Trio von Schlagzeuggrößen: Louis Hayes, Billy Hart und Cindy Blackman Santana.

Die Aufnahmen wurden neu von den originalen ¼-Zoll-Bändern überspielt und die Vinyl-Edition von Bernie Grundman gemastert.

ALBUM LINER NOTES

Even for Art Blakey, whose bands produced a trove of great in-person recordings over four decades, the music in this collection carries uncommon historical resonance. It captures one of the most celebrated Jazz Messenger units at the peak of its powers. As a marker of the band’s growing success and influence, First Flight to Tokyo also documents a pivotal moment in Messengers history.

Summarizing the evolution of Blakey’s band is a tricky business, for the constant comings and goings of musicians made even what are now considered classic Messenger configurations subject to flux. In the years leading up to this 1961 concert we can identify the period the drummer collaborated with Horace Silver as foundational, but that partnership established components of its signature hard bop style and made some of its own immortal live recordings before adopting the Jazz Messengers moniker. When Silver left to form his own quintet in mid-1956, Blakey’s personnel carrousel really started to turn. There was a year of some consistency with Bill Hardman on trumpet alongside either Jackie McLean or Johnny Griffin or both in the front line; but there were a succession of pianists including, on one occasion, Thelonious Monk, and there was scant evolution in either ensemble style or the band’s book. That changed in the summer of 1958, when Benny Golson became the saxophonist and musical director, bringing fellow Philadelphians Lee Morgan, Bobby Timmons and Jymie Merritt into the fold as well as a brace of memorable originals and a tighter ensemble focus. Yet by the time this quintet’s sole studio recording appeared to great commercial and critical success, Golson had moved on, in search of his own ensemble.

No sooner did Wayne Shorter emerge as Golson’s permanent replacement in the summer of 1959 than Timmons left to join the newly reformed Cannonball Adderley Quintet, a departure that turned out to be a mere six-month sabbatical. By February of 1960, Timmons was back in the fold, so that the band heard here had been together for nearly a year without a personnel change, a heretofore-unique experience in Messengers history. The musicians were locked in and prepared to stretch out, with a flow of fresh ideas that expand upon the familiar repertoire.

The present performances were captured at the end of a tour that resulted after Blakey was crowned in a Japanese magazine poll as the American musician that the country’s jazz fans were most eager to experience in person. Over the first two weeks of January 1961 the Messengers performed in several major Japanese cities and were received as artistic heroes wherever they appeared. This outpouring by the Japanese public, plus the concert and broadcast settings in which the band was presented, were a far cry from the treatment and working conditions commonplace in the USA and made a great impact on Blakey, who responded with a keen appreciation of his newfound role as international representative of his art form. If the Blakey/Silver partnership had established the Jazz Messengers style, and the tour Golson’s edition undertook at the end of 1958 introduced the band to European audiences, then this first visit to Japan made the Messengers a worldwide phenomenon and cemented what would prove to be its most loyal fan base.

Previous documents from the tour include a January 2 concert in Tokyo and a January 11 television appearance where the quintet was augmented by Nobua Hara’s Sharps and Flats big band. The present tracks, taped at the tour’s conclusion three days after the TV show, is notable in part for a heavy representation of modern jazz classics and the absence with the exception of “Dat Dere” of new Messengers music. A few of Shorter’s and Morgan’s more recently composed originals appear in the earlier Japanese performances, while this program places greater emphasis on titles that had become modern jazz warhorses. Blakey was hardly averse to programming new music, especially when recordings of live performances were planned; witness Meet You at the Jazz Corner of the World, taped at Birdland the previous September, when alumnus Hank Mobley was tapped for three compositions after new works by Morgan, Shorter and Timmons had been taped in Rudy Van Gelder’s studio the previous month. On this occasion, the emphasis was on allowing the band to create on material from earlier times as well as its current hits.

Golson’s “Blues March” and Timmons’ “Moanin’” were the titles that launched the then-current wave of Messengers popularity. They were included in every performance on the tour, received big band reinforcement by the Sharps and Flats on the television broadcast, and no doubt explain Blakey’s victory in the aforementioned magazine poll. “Dat Dere,” which composer Timmons recorded with both Adderley and Blakey, was a more recent creation that, like “Moanin’,” had already gained lyrics as well as several cover versions. As for the remainder of the program, Charlie Parker’s “Now’s the Time” and Dizzy Gillespie’s “A Night in Tunisia” were prominently featured on Blakey’s first live recordings, A Night at Birdland from 1954. The drummer was present when Thelonious Monk cut his first recording of “’Round Midnight” in 1947, although that classic appears not to have entered the Messengers repertoire until it became a feature for Morgan in 1960. Regardless of vintage, the quintet approaches each title with sizzling imagination.

Benny Golson’s “Blues March,” recorded originally in 1958 by Gigi Gryce and then Golson but made classic on the same October 30 session that introduced “Moanin’,” remained a Messengers staple for decades. Beyond its drum breaks, which were meat and potatoes for Blakey, it featured the parade ground bravura that was another aspect of African-American communal roots. The mood was also tailor-made for Morgan, who pianist Eddie Higgins had met three months earlier at a Vee Jay recording session and recalled 40 years later as “a little arrogant and cocky, like a young ballplayer who had hit a home run his first time at bat in the majors.” That assurance as well as Morgan’s playful nature comes through in a trumpet solo that fully embraces the march/shuffle groove and is typically studded with quotations, including a couple (“March of the Siamese Children,” “Peter and the Wolf”) that suggest Morgan was eager to extend the current tour to the Asian mainland. Shorter takes a far different approach, pushing just as hard but at an angle like a next-generation Lester Young before settling in for his own distinctive style of preaching. Timmons lets his influences shine through – Bud Powell phrases between breaths, Red Garland lines-to-chords trajectory – to which he adds a more sanctified profile. The performance fades out, an overused strategy in many studio recordings but more than fitting here, and expertly executed.

The first of two versions of “Now’s the Time” includes an incredible Shorter solo, with a two-note figure parsed like Sonny Rollins in “Blue Seven” mode; a more groove-oriented response by Morgan in which Shorter’s animating idea becomes cause to cite “In a Little Spanish Town;” and one of Timmons’ most personal efforts. This is Blakey’s feature, however, and he delivers two solos, including an introduction that lasts five minutes and a concluding statement after a few trades with the horns. While the ideas in the latter solo are clearly articulated within the blues structure, the opening is more of a leisurely articulation of Blakey techniques, as if the drummer were introducing himself and his strengths to his new Japanese friends.

The original Jazz Messengers recording of “Moanin’” was as influential as any single performance in launching the “soul jazz” trends of the late ‘50s. This performance, like most of the others documented by Blakey’s bands, contains the clearest example of the power of a hit, as Morgan opens and closes his solo with the same phrases he employed in the studio. Shorter, unlike Golson on the original, does not pick up the cue. Both Morgan and Timmons allude to “All This and Heaven, Too,” a quote also favored by Shorter in his Messenger years, and Jymie Merritt stretches out for a rare bass solo.

“’Round Midnight,” one of the concert’s “international standards,” features an arrangement that borrows from familiar sources while adding its own atmospheric introduction. Shorter and Timmons are relatively low-key in their brief improvisations, all the better to set up featured soloist Morgan. The trumpeter begins with seductive articulations in the horn’s lower register, and concludes his dramatic statement with a teasing minute-plus coda.

From the perspective of pure melody, “Dat Dere” is Bobby Timmons’ most indelible composition, one that had already inspired a brilliant lyric by Oscar Brown, Jr. Together with “Moanin’” and “This Here,” it probably made the pianist the most popular of Blakey’s sidemen at the time of the concert; but he remained a team player and a locked-in accompanist, as in his response to Shorter’s blunt solo entrance. Morgan brings the temperature down in his first chorus, marches in his second, and then swings out for his third, with the rhythm section in close support.

The second “Now’s the Time” finds Blakey reducing his opening solo by more than half and a more flowing Shorter. The saxophonist was seen at the time as a Coltrane acolyte, primarily based on the similarity of their urgent upper-register sound on the horn. That was just one aspect of Shorter’s evolving personal concept, although his ideas here build toward a suggestion of Coltrane’s sheets of sound. Morgan, who enters pecking and quickly escalates, shares solo honors with Timmons, in an extended outing filled with his more personal phrases and voicings.

“A Night in Tunisia” was as central to the Messengers’ profile as any other single composition. At the time of this recording, it had already served as the title track for two Blakey albums (RCA/Vik, 1957 and Blue Note, 1960) after being prominently featured on the 1954 Birdland recordings, where Blakey described having been present when Dizzy Gillespie composed the opus “in Texas, on the bottom of a garbage can.” While the 1960 studio version remains the best example of this bravura arrangement, with its interludes featuring all members on percussion, its flamboyant codas by Shorter and Morgan and deflating-balloon closing, this performance lacks nothing in the realm of excitement and ensemble virtuosity. Special mention should be made of Timmons, whose emphatic support lifts the horn solos into even loftier realms, and Merritt, whose walking choruses over the band’s slamming interjections sets up a drum barrage reminiscent of Blakey’s Orgy in Rhythm efforts. The true star, however, is the leader, who is at his most charismatic as both soloist, accompanist and team captain, telling Shorter to “whip it!” at one point.

Many of the adjectives frequently employed to describe Blakey might be in questionable taste given the disasters, both natural and man-made, experienced by the Japanese people, but the fans in Tokyo and throughout the country had no trouble embracing the power represented by his drums. Eddie Higgins, in the previously cited conversation, described the feeling generated by Blakey as “like a big fat firecracker up your behind.” Blakey, in turn, reciprocated the love with frequent return visits to Japan and a repertoire that soon included compositions titled “Ugetsu,” “On the Ginza,” “Kyoto” and “Nihon Bashi.” In the succeeding decade, when the Blue Note label had been sold and its new owners had temporarily shut it down in the USA, it was the Japanese fan base that effectively kept the label’s legend alive. Blakey used to love to say, “No America, no jazz,” and it could be equally claimed “No Japan, no revival of Blue Note Records.” Arigato, Japan. Arigato, Art Blakey.

Bob Blumenthal

Radio-Kontakte

Media Promotion

Rosita Falke

info@rosita-falke.de, Tel: 040 – 413 545 05

Blue Note Records / Universal Music

2-CD 06024 3595285 / 2-LP 06024 3595286

NEUER VÖ: 10.12.2021